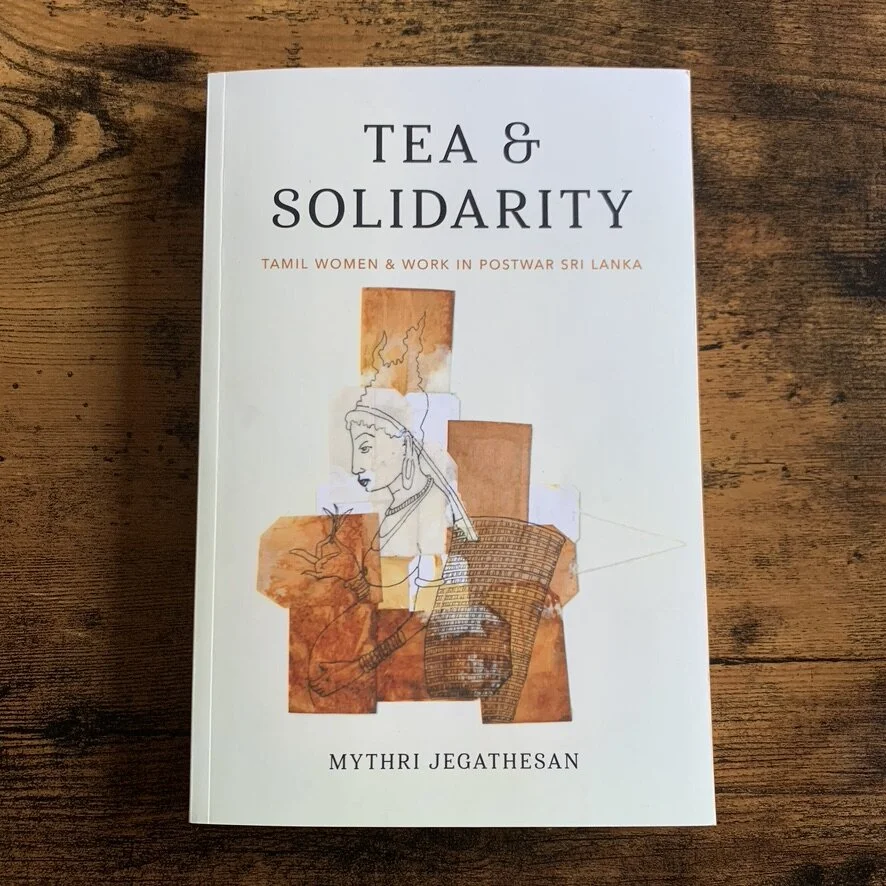

Tea and Solidarity: Tamil Women and Work in Postwar Sri Lanka

(University of Washington Press, 2019)

Tea and Solidarity is an ethnography of plantation life and work in the context of ethnonationalist politics and civil war in Sri Lanka. It documents workers’ desires and movements for dignified work and their ongoing struggles for labor and gender justice during and after Sri Lanka’s twenty-six year long civil war.

Tea and Solidarity was awarded the 2020 Diana Forsythe Prize for the best book featuring feminist anthropological research on work, science, or technology, including biomedicine and Honorable Mention for the 2020 Society for the Anthropology of Work Book Prize. Since its publication, it has been taught in anthropology, gender, international development, and South Asian studies courses at University of Washington, St. Olaf College, American University, University of Colombo, Yale University, York University, City University of New York (CUNY), University of Colorado-Colorado Springs, and Santa Clara University. A South Asia edition of the book is available for purchase with Tambapanni Academic Publishers (Colombo, Sri Lanka).

To read engagements with the book by scholars of labor and work, please see the Society for the Anthropology of Work (SAW) Book Forum here and also this video commentary and academic analysis of the book directed and produced by Clay Bowen.

Excerpts from reviews of Tea and Solidarity

“Jegathesan’s ethnography is cast in a mode that can reach her participants, who will recognise themselves within a narrative that renders visible Hill Country Tamil women workers’ affective and material struggles to build viable worlds for themselves and their families, even as they confront a multitude of adversities”

-South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies (2022)

“Jegathesan deftly shows how the data regimes which count and categorize plantation life often miss the forms of accounting most salient for plantation workers themselves . . . Tea and Solidarity is a moving account of the value of women’s work, not as mere accumulation by dispossession but as testament to the durability of life itself. For those who love Ceylon tea, this book is a must read. It is an important resource for anyone concerned with the politics of work, science, and technology. Jegathesan shows that it is possible to expose past records of violence, and ongoing injustices, while pushing for more equitable ways of living and being.”

-The 2020 Diana Forsythe Prize Selection Committee

“Tea and Solidarity reinvigorates conversations in feminist political economy and presents an exciting and inspiring example of the richness of the anthropology of work today. It is attentive to, and reflexive about, the importance not only of storytelling but also of the kinds of stories we tell as anthropologists and how we do that telling.”

-Anthropology of Work Review (2020)

“Tea and Solidarity is an excellent read and provokes an engagement with such issues as positionality, situated knowledge, ethical responsibilities as researchers, and more importantly the transformative potential of transnational rights-based interventions. By focusing on ‘how gender, work and value making shape Hill-Country Tamil Women’s lives’, Jegathesan shifts the terms of feminist engagement to stand in solidarity with them.”

-Gender, Place and Culture (2021)

“Mythri Jegathesan’s Tea and Solidarity is a work of deep intellectual, emotional, and embodied engagement with her interlocutors and the landscapes imbued with their histories and desires. The ethical and political commitments that guide the author’s research praxis are equally salient in her evocative writing. In conveying the textures of experience—her interlocutors’ and her own—Jegathesan lays bare the affective and relational processes through which ethnographic insights emerge. The analysis brings together the scholarly and everyday registers of language and theory as well as tacit forms of knowledge to deconstruct the tea plantation as a place of imperial nostalgia and to engender new ways of thinking about and seeing the past and present of the Hill Country Tamil community within Sri Lanka.”

-Polity (2021)